The Viral Visuality of Memes: Some Afterthoughts on the Visual Contagions Conference

Virality is everywhere in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Not just literally, in the form of floating viruses, but because of the (mis)information that spreads through social media as if it was viral itself. Nowadays, everybody seems to be a virologist or at least has some knowledge about viruses. Social science and humanities do research on virality, much as biology and medicine do. Last year, I myself published a paper on memes of the virus. Of course, thinking about virality is not a new phenomenon for social science or humanities. It actually dates back at least to mass psychologist Gustave Le Bon’s social contagion research. According to Paul Marsden, memes closely relate to social contagion. But, is this true for internet memes and viral content as well?

This is the question I addressed in my paper for the international conference Visual Contagions through the Lens of New Media, organized by Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Thibaut Vaillancourt, Anthony Bekirov and Rui-Long Monico and set to take place in Geneva, but relocated – almost ironically – online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In my video, which I produced beforehand, I examined the history of memes and the media practice of memeing, from retracing the origins of the term ‘meme’ in evolutionary biology to examining how the term has semantically evolved over time on the internet.

My paper starts with the evolutionary biologist and famous atheist Richard Dawkins, who coined the term ‘meme’ in 1976 in his bestselling book the The Selfish Gene. In his view, memes are literally viruses that infect the human mind with culture, most powerfully in the form of religion. I argue that his concept of memes is hardly scientific, and in fact was scientifically disputed many times. Rather, Dawkins uses his notion of memes normatively to justify his criticism of religion. Nevertheless, memetics developed into its own field of research that more or less successfully tried to explain culture through viral contagion. For example, media scholar Douglas Rushkoff believes that “media events are not like viruses. They are viruses.”

Later, on the internet, cultural phenomena were called memes, however much more sporadically as today at first. Moreover, what was initially called memes, like the Dancing Baby or Godwin’s Law, has little in common with later internet memes. The term began to change when it was adopted on 4chan around 2004. At the time, the population of 4chan mainly consisted of former members from Something Awful, an internet forum, which evidently hated the concept of memes, but ironically is responsible for the first internet phenomena that were later historicized as internet memes. On Something Awful, these early internet phenomena were called image macros instead. In this concrete form, internet memes were widely popularized worldwide.

At least since 2014, image macro memes became out of fashion and where declared dead. But actually, internet memes were never more popular than today. In 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, internet memes thrived like never before, which indicates that the concept of memes just has evolved once again.

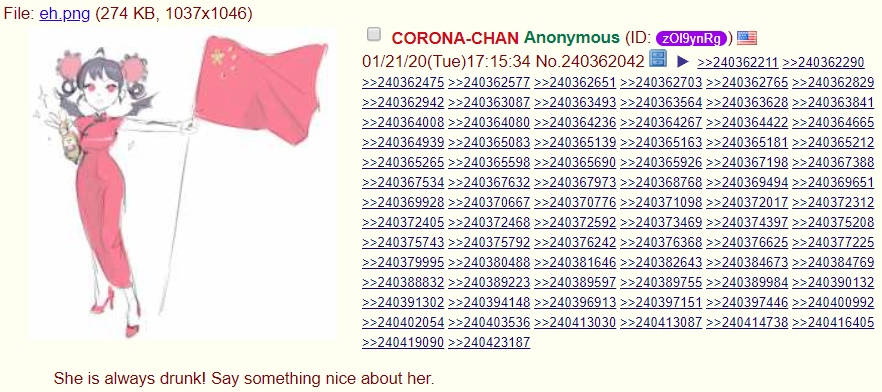

Corona-chan is the first meme of the virus that reflects on the pandemic by picturing the corona virus in the form of an anthropomorphized anime girl. In regard of the term ‘meme,’ it is interesting to see that Corona-chan is much more loosely conceptualized as an internet meme as were image macros before. Nowadays, the noun ‘meme’ is often turned into an adjective like “meme-y” or a verb like “memeing.” As a media practice, memeing means that users can only create and share memes within certain structures of meme culture such as, for example, rules of a subreddit stating that Corona-chan should be portrayed “in an artistic/memey fashion.”

It remains to be seen, how the term ‘meme’ and the media practice of memeing will further change in the future. I suspect that memes are becoming a digital art form that is located in and afforded by meme culture. In case of Corona-chan, memeing is no longer just everyday communication, as most image macros are, but an artistic expression based almost entirely on visual aesthetics. Memes are not dead, but actually become more visual. As I argued elsewhere, dank memes are a visual criticism on the textuality of image macros. After 20 years of speech-based memes, now the image seems to be on the forefront of meme culture.

At the conference, Max Bonhomme lamented the lack of visual analysis on memes. In his paper, he suggests that the visual roots of memes can be traced back to the 16th century, when criticism was expressed through so-called “Schandbilder.” Memes do also resemble Dadaist photomontages à la John Heartfield, which reflect on image-making practices in a similar way as memes do. These art historical roots can explain why internet memes are literally designed to be visual: the mass-produced image affords spreadability. For the digital image, this is even more true. Memes seem to ‘go viral’ on the internet, but actually are just massively shared online.

Memes do not spread because they are literally infectious but because they rely on semiotic practices as Gabriele Marino argues. In his view, semiotics seems to be destined for analyzing memes because memeing is based on meaning-making practices such as sharing, sampling and remaking of digital content. Semioticians need to study memes to keep up with popular culture much like Roland Barthes and Umberto Eco once did.

Marino emphasizes that when we talk about memes, we always mean two things: digital images on the on hand, textual formulae on the other hand. Because of this dialectic, internet memes can be best understood multi-disciplinarily, through the lenses of media studies, ethnography, art history, semiotics, and other social sciences and humanities. The rich program of the conference, which was not just about internet memes, even if they loomed large, but about games and digital art as well, made such multiperspectivity possible.

Besides the academic papers, in the pauses artistiques, artistes had the chance to present their perspective on the digital image, too. Before the conference, all presenters received real postcards by “a chatbot named Gu-11-vR” that explored the depths of the internet as part of the exhibition Postcards From the Internet by Robin Champenois. According to the AI, internet memes are “widespread and specific to the Web” and “have a high artistic quality.” I want to add that memes are also a perfect representation of the digital image since memes are made of and reflect on digital photographs, game and video screenshots, digital and digitalized artworks. These forms of digital media are remediated by memes to become part of social media. This means that digital media can be studied through memes, but more importantly that memes need to be studied “through the lens of new media” as proposed by the conference.

Schreibe einen Kommentar

Du musst angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar abzugeben.