Reading the source code for Adobe Photoshop (part I)

Critical Code Studies

For my project on digital image processing, I will not only look at the ‘surface’ of Adobe Photoshop (i.e. its interface, its paradigmatic functions, typical uses and effects). I will also try to analyze and interpret what ‘lies beneath’ the program: its source code.

But why should I—a humanities academic trained in the history and theory of media, not a computer scientist or software engineer—want to read the ‘underlying text’ of a computer program? And how can I hope to understand it and make any substantial claims about it?

For some time now, Critical Code Studies (CCS) have advocated the idea of a ‘hermeneutics of code’—of reading computer code as a cultural text, concentrating on its “extra-functional” aspects and cultural implications. The goal of CCS is, in the words of its most prominent champion, Mark C. Marino, “to learn to understand not only the functioning of code but the way code signifies”.1 In CCS, “computer code serves as the entry point to explorations of digital culture”. The source code for Adobe Photoshop, it follows, promises to act as a window on the culture of digital image processing and digital visual culture at large.

Over the last few years, scholars in CCS have presented us with some exemplary code studies on various pieces of software. There has also been prominent criticism of the idea that source code constitutes some kind of privileged object for the study of digital culture.

In spite of its ambitious goals, however, CCS has so far remained a rather peripheral and modest phenomenon within the wider field of digital media studies. The actual analyses that I am aware of are all of quite small programs or short passages of programs, sometimes of just a single line of code. To my knowledge, no one has ever attempted a critical code study of a complete commercial application comparable in size and significance to Adobe Photoshop.

Source code

One of the reasons why CCS has shunned ‘big’ programs might be that the source codes for most commercial programs are closely-guarded secrets of the companies owning the rights and are not shared with the public. In the case of Photoshop, however, Adobe has made available the code for one of the earliest versions of the program through the Computer History Museum website in 2013.2 Of course, Photoshop has seen no less than 18 major iterations since its launch in 1990 and the original code base published by Adobe has long since been put out of commission. Still, anyone can now take a close look at the program’s source code as it was initially written for version 1.0.1 for Apple Macintosh Computers in 1990 and see exactly how the ‘digital image manipulation revolution’ was implemented.

Very shortly, what is source code? Simply put, it is the human-readable ‘text’ of a computer program written in some programming language by its human author(s) that is then automatically translated into the executable form of the program (binary machine code) before it can be run on a computer. For various reasons, the source code for Photoshop 1.0.1 cannot easily be translated into an actual running application today. Still, we have access to the code and can read it and try to make some sense of it.

In what follows, I will look at the source code for Photoshop 1.0.1 and see how far one can get in interpreting it with minimal technical knowledge and using only simple tools. This is an important point for my project and, I think, for CCS in general. While CCS champion Marino notices that “programming literacy” is “[k]ey to critical code studies,”3 I want to argue that humanities scholars should not have to become proficient programmers in order to practice CCS.

Programming literacy

Of course, reading code requires at least a basic understanding of the language in which the code is written. Just as philology without literacy in the respective natural language is a self-contradiction, CCS without literacy in the respective programming language is an impossibility. But it is one thing to be able to read, say, The Song of Roland in Old French or the Epic of Gilgamesh in Akkadian and quite another thing to be able to produce works of similar literary quality in these languages. Certainly, we do not expect philologists to accomplish such feats. And neither should we expect CCS scholars to develop the next Adobe Photoshop or Firefox Browser.

Also, since the ‘expressive’ potential of programming languages is much smaller than that of natural languages (mostly due to the syntactic limitations), the reading skills necessary for CCS may be much lower than those required for scholarly literary analysis (perhaps more like an A2, B1 or B2 level in the CEFR).

Furthermore, Rieder has argued that “[k]nowing how to read code is rarely sufficient to understand the actual content of a program” as the program’s “domain of function” by far exceeds the complexity of its code.4 If this cautionary remark proves true, it might actually play into the hands of CCS practitioners. What we are after in CCS lies mostly ‘outside’ the code anyway. For when humanities scholars try to read and interpret the source code of an imaging application, they are really interested in questions about the status of digital images, transformations of photographic practices, the changing nature of visuality and so on. And these are not merely ‘technical’ but eminently cultural issues. Remember: The program’s source code is supposed to act only as a ‘point of entry’ into or as a window on digital culture.

Consequently, I trust that my lack of formal training in computer programming will not pose a serious problem for my attempt at reading the source code for Photoshop. Full disclosure: Although I did enjoy a half-year course on Pascal in high school back in the 1990s, I am only self-taught in fundamentals of programming and in a few select languages at a beginner’s level. What I understand about code like the one for Photoshop 1.0.1 rests upon this rudimentary knowledge and what further resources on programming such applications at the time I can find on the Internet.

So, do not expect a profound analysis of the internal details of Photoshop, no in-depth discussion of particular algorithms or data structures or anything of the kind (certainly not right away). Also, I do not think that I will make any astonishing findings in the code at the outset of my study (and maybe not ever). I do not know whether there are any ‘hidden gems’ buried in Photoshop’s source just waiting to be discovered. For a start, I hope for nothing more than a general idea of the program’s design, a first survey of the code which will give me a preliminary map to guide the following steps of the analysis.

Where to start?

Unlike the smaller programs and shorter excerpts of code that CCS has mostly concentrated on so far, Adobe Photoshop 1.0.1 presents us with the particular problem of where to begin reading the code. After all, even the first release of the program comprises tens of thousands of lines of source code (more on that in a moment). In principle, we could dive right into the source at any point we choose or, conversely, try to find the ‘actual beginning’ of the program in the code and proceed from there. However, both these approaches are highly problematic.

The size and architecture of the program resist both the type of linear, exhaustive reading we might give a novel and also—initially, at least—the random singling out of individual parts. As CCS practitioners, we cannot hope to read and comprehend the program in its entirety from beginning to end. And neither can we hope to understand and interpret its contribution to digital visual culture by picking arbitrarily at individual bits. We need an overview of the ‘program text’, a layout of the source code that lets us decide where to put the focus after an initial cursory assessment.

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines in CCS on how to approach ‘big’ software like Adobe Photoshop. To my knowledge, CCS has nothing to say about what strategies and what tools to use when tackling very large codebases. So far, there exists no methodical framework for the analysis and interpretation of PC consumer applications at the level of the source code in CCS. Therefore, I will just have to make it up as I go along.

Files

First, let us see what the source code actually looks like when you access it through the Computer History Museum website.

After having agreed to the CHM’s license agreement, you can download a ZIP file named photoshop-v.1.0.1-source-code.zip. Unpack this archive and you are presented with a large number of files:

About.r UEPSFormat.p UPressure.p

AcquireInterface.p UFilter.p UPrint.p

Black.r UFilter.p.inc UPrint.p.inc

ChangeHistory.txt UFilters.a UProgress.inc1.p

ExportInterface.p UFilters.a.inc UProgress.p

FilterInterface.p UFilters.inc1.p URawFormat.inc1.p

Huffman.p UFilters.p URawFormat.p

Huffman1.r UFloat.a UResize.a

Huffman1.t UFloat.a.inc UResize.a.inc

Huffman2.r UFloat.p UResize.inc1.p

Huffman2.t UFloat.p.inc UResize.p

MPhotoshop.p UGIFFormat.a UResize.p.inc

MovableWDEF.make UGIFFormat.a.inc URootFormat.inc1.p

MovableWDEF.p UGIFFormat.inc1.p URootFormat.p

PaletteWDEF.make UGIFFormat.p URotate.a

PaletteWDEF.p UGhost.inc1.p URotate.a.inc

Photoshop.make UGhost.p URotate.p

Photoshop.r UGhost.p.inc URotate.p.inc

PixelPaint.r UHistogram.p UScan.p

Tables.p UHistogram.p.inc UScan.p.inc

Tables.r UIFFFormat.a UScitexFormat.inc1.p

Tips.p UIFFFormat.a.inc UScitexFormat.p

Tips.r UIFFFormat.inc1.p UScreen.a

UAbout.a UIFFFormat.p UScreen.a.inc

UAbout.a.inc UInitFormats.p UScreen.inc1.p

UAbout.p UInitFormats.p.inc UScreen.p

UAbout.p.inc UInternal.inc1.p UScreen.p.inc

UAdjust.a UInternal.p USelect.a

UAdjust.a.inc UInternal.p.inc USelect.a.inc

UAdjust.inc1.p ULZWCompress.inc1.p USelect.inc1.p

UAdjust.p ULZWCompress.p USelect.p

UAdjust.p.inc ULine.a USelect.p.inc

UAssembly.a ULine.a.inc USeparation.a

UAssembly.a.inc ULine.p USeparation.a.inc

UBWDialog.inc1.p ULine.p.inc USeparation.inc1.p

UBWDialog.p UMacPaint.inc1.p USeparation.p

UCalculate.a UMacPaint.p USeparation.p.inc

UCalculate.a.inc UMagnification.p UTIFFormat.a

UCalculate.p UMagnification.p.inc UTIFFormat.a.inc

UCalculate.p.inc UPICTFile.inc1.p UTIFFormat.inc1.p

UChannel.p UPICTFile.p UTIFFormat.p

UChannel.p.inc UPICTResource.inc1.p UTable.p

UCommands.inc1.p UPICTResource.p UTable.p.inc

UCommands.p UPasteControls.p UTarga.a

UConstants.p UPasteControls.p.inc UTarga.a.inc

UConvert.a UPhotoshop.inc1.p UTarga.inc1.p

UConvert.a.inc UPhotoshop.p UTarga.p

UConvert.p UPick.p UText.p

UConvert.p.inc UPick.p.inc UText.p.inc

UCoords.p UPixar.inc1.p UThunderScan.inc1.p

UCoords.p.inc UPixar.p UThunderScan.p

UCrop.p UPixelPaint.inc1.p UTransfer.inc1.p

UCrop.p.inc UPixelPaint.p UTransfer.p

UDither.a UPostScript.a UTrap.a

UDither.a.inc UPostScript.a.inc UTrap.a.inc

UDraw.a UPostScript.inc1.p UTrap.p

UDraw.a.inc UPostScript.p UTrap.p.inc

UDraw.p UPreferences.p UVMemory.inc1.p

UDraw.p.inc UPreferences.p.inc UVMemory.p

UEPSFormat.inc1.p UPressure.inc1.pAs the website hosting the code has already informed us, there is a total of 179 files in the ZIP archive. (Check with your favorite file browser or do a quick count using the basic Unix tools ls and wc on the command line with $ ls -1|wc -l.) This is to be expected. For reasons of convenience and modularity the source code even of quite modest programs is routinely split up into several files.

Now, what are those 179 files about? Instead of going through the contents of each file one after the other, let us first try to do a kind of very basic ‘distant reading’ of the Photoshop source code as a collection of files. Even before looking inside individual files and examining the code in detail we can glean some useful information abut Photoshop’s source just by looking at the names of the files and their sizes (and, possibly, at a directory structure which is missing in this case, however).

Filenames

Most of the filenames at least hint at what the code contained within relates to. Several files seem to correspond directly to specific image editing functions of the program like cropping, resizing or rotating images (UCrop.*, UResize.* and URotate.*). Others probably implement the file formats supported by this early version of Photoshop like EPS, GIF and TIFF (UEPSFormat.*. UGIFFormat.* and UTIFFormat.*). Still other names point at the techniques and algorithms used in processing and storing image data (ULZWCompress.* or UVMemory.*). Then, there are five files that carry the name of the program proper (MPhotoshop.p, Photoshop.make, Photoshop.r, UPhotoshop.inc1.p, UPhotoshop.p). Only a handful of filenames are so generic or enigmatic (Black.r, Tables.* or UGhost.*) that we cannot guess right away what the code might be about. One thing that stands out when looking at the filenames is that the majority, 156 files to be exact (file browser or $ ls -1 U*|wc -l), starts with an upper case ‘U’ as in UCrop.*, UGIFFormat.* and UVMemory.*. We will return to this peculiarity in the next installment of this series of blog posts.

Apparently, the source code for Adobe Photoshop is structured into individual files along the boundaries of particular features, interfaces and internal ‘mechanisms’ of the program. This structure not only indicates one of the two major programming paradigms that Photoshop follows (and which, unsurprisingly, is called structured programming). It may also prove helpful later on in our critical code study as it allows us to significantly narrow down the amount of code we have to examine when analyzing select parts of Photoshop.

Next, we want to take a look at the filename extensions. Every file in the source code archive has a suffix to its name like .p or .r denoting the type of the file. Again, we have already been told on the CHM website that Photoshop was written mainly in the programming language Pascal with some additional parts coded in assembly instructions for the Mac’s Motorola 68000 CPU. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the filename extension .p stands for Pascal source files whereas .a stands for assembly language files. A quick count (file browser or $ ls -1 *.p|wc -l; ls -1 *.a|wc -l) shows 94 .p to 21 .a files, a ratio that supports this assumption. (In fact, files ending in .inc are also Pascal language files, bringing the Pascal to assembly file ratio to 144:21.)

Languages high and low

A peek inside two corresponding files (URotate.p and URotate.a) confirms our hypothesis about the correlation of filename extension and programming language.

This is what Pascal looks like (lines 1602 to 1645 from URotate.p with empty lines removed):

FUNCTION DoRotateCommand (view: TImageView; angle: INTEGER): TCommand;

VAR

doc: TImageDocument;

aRotateImageCommand: TRotateImageCommand;

aRotateFloatCommand: TRotateFloatCommand;

BEGIN

IF angle = 1800 THEN

DoRotateCommand := DoFlipCommand (view, TRUE, TRUE)

ELSE

BEGIN

doc := TImageDocument (view.fDocument);

IF EmptyRect (doc.fSelectionRect) THEN

BEGIN

NEW (aRotateImageCommand);

FailNil (aRotateImageCommand);

aRotateImageCommand.IRotateImageCommand (view, angle);

DoRotateCommand := aRotateImageCommand

END

ELSE

BEGIN

NEW (aRotateFloatCommand);

FailNil (aRotateFloatCommand);

aRotateFloatCommand.IRotateFloatCommand (view, angle);

DoRotateCommand := aRotateFloatCommand

END

END

END;Notice the high-level language elements like variables and functions with descriptive names (like DoRotateCommand and angle) and conditional statements like IF … THEN … ELSE.

On the other hand, this is what assembly code looks like (lines 12 to 57 from URotate.a with empty lines removed):

SEG 'ADoRotate'

DoReverseBytes PROC EXPORT

; Calling sequence (Pascal conventions):

;

; PROCEDURE DoReverseBytes (data: Ptr;

; count: INTEGER);

;

; Parameter Offsets

@data EQU 10

@count EQU 8

; Size of parameters

@params EQU 6

; Unload parameters

LINK A6,#0

MOVE.L @data(A6),A0

MOVE.W @count(A6),D0

; Compute address of one pixel past last

MOVE.L A0,A1

ADDA.W D0,A1

; Reverse the bytes

ASR.W #1,D0

SUB.W #1,D0

BMI.S @2

@1 MOVE.B (A0),D1

MOVE.B -(A1),(A0)+

MOVE.B D1,(A1)

DBF D0,@1

; Clean up and exit

@2 UNLK A6

MOVE.L (SP)+,A0

ADD.W #@params,SP

JMP (A0)Notice the repetitive use of short mnemomics for low-level 68K Motorola machine instructions (like MOVE.*, ADD.* and SUB.*) and the addressing of CPU registers (such as A0 and D0).

The difference between high-level language source in Pascal and low-level machine instructions also shows in the fact that the assembly code contains several comments explaining what is going on (in lines starting with a semicolon, e.g. Compute address of one pixel past last) while the more abstract but descriptive Pascal source seemingly needs no further explanation.

.inc, .make, .r and .t

I will discuss the qualitative differences between Pascal and assembly language with regard to Photoshop’s source in the follow-up to this blog post. But now let us conclude our short survey of filename extensions.

Wikipedia has a comprehensive list of filename extensions we could check for the remaining suffixes .inc, .make, .r, .t and .txt. In this case, however, it is not much help. Whereas .txt is well-known and only used once for the pretty self-explanatory file ChangeHistory.txt, none of the four remaining suffixes is covered by Wikipedia. So we will have to help ourselves and examine the files to make sense of them.

All of the .inc files are only a few lines long and do not seem to contain anything other than references to functions and procedures defined or called in the Pascal source files. Therefore, they can probably be treated and counted as some kind of addition to the main Pascal files (or simply ignored because they do not contain information meaningful to our analysis).

Of the three .make files, Photoshop.make is the important one. It references the other source files of the code like this (lines 71 to 82):

UPhotoshop.p.o : UConstants.p UVMemory.p UBWDialog.p UProgress.p \

UAbout.p.inc UAdjust.p.inc UAssembly.a.inc \

UCalculate.p.inc UChannel.p.inc \

UConvert.p.inc UCoords.p.inc UCrop.p.inc \

UDither.a.inc UDraw.p.inc UFilter.p.inc UFloat.p.inc UGhost.p.inc \

UHistogram.p.inc UInitFormats.p.inc UInternal.p.inc \

ULine.p.inc UMagnification.p.inc \

UPasteControls.p.inc UPick.p.inc UPreferences.p.inc \

UPrint.p.inc UResize.p.inc \

URotate.p.inc UScan.p.inc UScreen.a.inc UScreen.p.inc \

USelect.p.inc USeparation.p.inc UTable.p.inc UText.p.inc \

UTrap.p.incApparently, Photoshop.make is some sort of makefile that ties all of the source files together and tells the compiler how to build the application ready to be run by users. And while it contains no algorithms or other code constructs of particular interest to us, we do learn one more thing from Photoshop.make. Lines 31 to 33 tell us that the source files ending in .r are “RezFiles”:

OtherRezFiles = "{RIncludes}"SysTypes.r \

About.r Black.r Huffman1.r Huffman2.r \

PixelPaint.r Tables.r Tips.rA look inside one of those files shows data encoded in hexadecimal form like this (lines 8 to 18 from UAbout.r):

resource 'PICT' (700, purgeable)

{

18908,

{0, 0, 220, 500},

$"0011 02FF 0C00 0000 49DC 0000 0000 0000"

$"0000 00DC 0000 01F4 0000 0000 0000 0001"

$"000A 0000 0000 00DC 01F4 0098 80FA 0000"

$"0000 00DC 01F4 0000 0000 0000 0000 0048"

$"0000 0048 0000 0000 0004 0001 0004 0000"

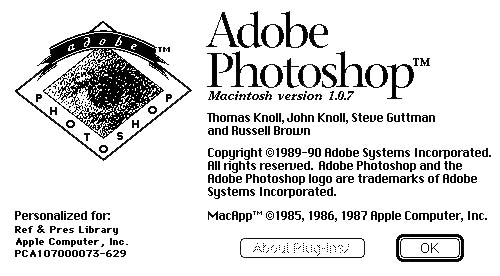

$"0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000"“PICT” probably stands for “picture” and the hex-encoded data in UAbout.r is probably the bitmap for the program’s “About Photoshop…” dialog also shown on the CHM website (although for version 1.0.7):

Finally, the two files ending in .t (Huffman1.t and Huffman2.t) contain two tables of integers ranging from 1 to 2560 (with a lot of omissions above 64) assigned to variable-length binary numbers—evidently a Huffman code for lossless data compression.

To summarize:

.a,.pand.incfiles make up the Pascal and assembly language code of the program;.rand.tfiles contain data (encoded in one form or another);.makefiles tie the source together so the final program can be built from it;- the

.txtfile contains human-readable information about changes to the first (pre-)release versions of the program.

Size of the code

As the last step in our initial survey or ‘distant reading’ of Photoshop’s source, we want to look at the size of the code.

To get a general feeling for the size, let us first simply compare files. Of the ten largest files in the source archive (file browser or $ ls -1Sl|head), six are Pascal language files, two are “Rez” files and one is an assembly file (the fifth column from the left shows the file size in bytes):

total 3024

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 222910 19 Jan 2013 Photoshop.r

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 214900 19 Jan 2013 UPhotoshop.inc1.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 104390 19 Jan 2013 UDraw.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 93302 19 Jan 2013 UAdjust.inc1.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 76349 19 Jan 2013 USelect.inc1.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 73128 19 Jan 2013 About.r

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 72149 19 Jan 2013 UFloat.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 71974 19 Jan 2013 URotate.p

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 67964 19 Jan 2013 USeparation.aThe largest file overall is the “Rez” file Photoshop.r (at about 218 kilobytes), so we will definitely take a closer look at it later on in our analysis. The smallest of the top-ten is the assembly file USeparation.a (at about 66 kilobytes).

The ten smallest files ($ ls -1Sl|head) are all .inc files only a handful of lines long:

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 486 19 Jan 2013 UText.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 480 19 Jan 2013 UScreen.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 473 19 Jan 2013 UTable.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 454 19 Jan 2013 ULine.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 444 19 Jan 2013 UPreferences.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 431 19 Jan 2013 UPasteControls.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 412 19 Jan 2013 UTrap.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 396 19 Jan 2013 UAbout.a.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 357 19 Jan 2013 USeparation.p.inc

-rw-r--r--@ 1 till staff 355 19 Jan 2013 UInitFormats.p.incThe Pascal files total about 2 megabytes (file browser or $ du -ch *.p), the assembly files about 388 kilobytes ($ du -ch *.a) and the ‘data’ files .r and .t about 384 kilobytes ($ du -ch *.r *.t). Therefore, the file size ratio of Pascal to assembly to data is about 72% to 14% to 14% or roughly 5:1:1.

Lines of code

File sizes are a decent indicator of code size. But the most common metric for measuring the size of a software project is the number of ‘lines of code’ (LOC), sometimes also called ‘source lines of code’ (SLOC). Generally speaking, one line of code corresponds to one statement or ‘command’ in a given language. (Although the style of the language and also of the programmer complicate things a lot.)

We can get a quick and dirty total of ‘physical’ LOC using the Unix tool wc: The command $ wc -l *.p *.inc *.a counts all lines in the Pascal and assembly language files and gives a result of 116.587 lines. But source files often include lines containing only programmers’ comments and also empty lines which are used to visually organize the code and make it more legible. Again, take a look at URotate.a (lines 10 to 28):

; **********************************************************************

SEG 'ADoRotate'

DoReverseBytes PROC EXPORT

; Calling sequence (Pascal conventions):

;

; PROCEDURE DoReverseBytes (data: Ptr;

; count: INTEGER);

;

; Parameter Offsets

@data EQU 10

@count EQU 8

; Size of parameters

@params EQU 6Of these nineteen lines of assembly code, only five should actually be counted as LOC (lines 12, 14, 23, 24 and 28) as the others do not contain any instructions to the machine.

Excluding empty and comment lines with tools like wc is tricky. So we better use a dedicated program. A very good choice for counting LOC—although not the most modern or fastest one—is the free and open-source program cloc. One advantage of cloc is that you can tell it to process files in a particular programming language. With a few well-chosen arguments we can include .a as assembly and .inc as additional Pascal files (.p files are recognized automatically as Pascal source) but exclude .r files which cloc would otherwise mistakenly identify as belonging to the processing language R.

The command $ cloc --force-lang="Assembly",a --force-lang="Pascal",inc --exclude-ext=r * shows us this result:

179 text files.

179 unique files.

14 files ignored.

github.com/AlDanial/cloc v 1.88 T=0.89 s (185.0 files/s, 130748.7 lines/s)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pascal 144 32070 2767 63004

Assembly 21 4867 5651 8228

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 165 36937 8418 71232

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------As you can see, the totalized sum of blank, comment and code lines given by cloc equals the 116.587 lines we got using wc.

But cloc tells us considerably more. Using the specialized tool we find that more than half of the lines in Photoshop’s assembly files are blank lines or comments and that, likewise, about a third of the lines in the Pascal files are empty and only used to visually structure the code. cloc also confirms our first impression that Photoshop’s assembly part is more heavily commented than its Pascal counterpart: Whereas the comment to code ratio is about 6:7 in assembly files, it is only 1:23 in Pascal files. Also, counting only lines of actual code, the ratio of Pascal language to assembly language is not 5:1 (as we originally assumed on the basis of file size alone) but more like 10:1! Excluding the .make, .r and .t files and factoring in assembly and Pascal LOC only, Photoshop’s source is 88% Pascal.

Finally, some words on the overall size of Photoshop’s source code. Counting all the physical lines in all files, including blanks and comments ($ wc -l *.a *.inc *.make *.p *.r *.t), we get a total of 128.602. Compared to current PC applications this seems tiny: The source code for Mozilla’s Internet browser Firefox has 21 million lines of code, more than 160 times the amount of Photoshop’s LOC! However, software size has exploded since the early 1990s and in contrast to today’s team- or even crowd-based software development, Photoshop was written primarily by a single software engineer, Thomas Knoll. A better benchmark, therefore, may be a program like MacPaint, the seminal graphics editor written for the original Apple Macintosh in 1984 by Bill Atkinson, only six years before Photoshop’s release. According to the CHM website hosting the source code for MacPaint, the program measures a mere 9.405 physical LOC. Photoshop, we may conclude, was probably a large program by the standard of the day. In any case, more than one-hundred thousand lines is certainly more than enough for us to tackle in a critical code study.

Conclusion and preview

Of course, nothing we have done so far amounts to a substantial analysis of the actual source code of Adobe Photoshop—least of all to a critical code study of the program.

But with our initial ‘distant reading’ of the code we have taken the important first step of gaining an overview of the source archive, of getting a general idea of the code’s structure, of the languages used and of how the program is distributed in parts across individual files. We have identified the central .make file which ties everything together for compilation and also the table and “Rez” files which contain encoded data of various sorts. From the filenames and occasional peeks inside this and that file, we have gotten an idea where to look for sections of the code concerning specific functions or components of the program. And we have done so using nothing more than very simple instruments like common file browsers and basic Unix command-line tools plus one dedicated programm to count LOC and some additional resources that can easily be found on the Internet.

Next time, we will talk about the Pascal and assembly language used for Photoshop, see if we can extract more information from the source files with the help of standard Unix command-line tools and maybe even start poking and prodding at select pieces of code. So, if you are interested, please come back for part II in November! In the meantime, I am looking forward to your comments, questions and suggestions.

Notes

- Mark C. Marino: Critical Code Studies, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 2020, p. 5.↩︎

- On the CHM website you can also find the source codes for early versions of other popular programs like MacPaint, Word for Windows and the Eudora Mail Client.↩︎

- Marino: Critical Code Studies, p. 45.↩︎

- Bernhard Rieder: Engines of Order: A Mechanology of Algorithmic Techniques, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2020, pp. 14, 98.↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.